At Eternity’s Gate

Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), one of the most beloved and iconic artistic figures in history, has been the subject of numerous films, including Loving Vincent (2017), Vincent van Gogh: A New Way of Seeing (2015), Maurice Pialat’s Van Gogh (1991), Robert Altman’s Vincent and Theo (1990), Vincent (a 1987 documentary by Paul Cox) and Vincente Minnelli’s Lust for Life (1956), among others.American artist and filmmaker Julian Schnabel’s At Eternity’s Gate is the latest treatment of the painter’s life. It focuses on van Gogh’s last years, from 1887 to 1890. Schnabel has created thoughtful works, such as Before Night Falls (2000), about Cuban poet Reinaldo Arenas, and Miral (2010), the story of a Palestinian girl coming of age in Israel during the First Intifada.

At Eternity’s Gate is co-written by Schnabel, Louise Kugelberg and Jean-Claude Carrière. Eighty-seven-year-old Carrière is known for his 19-year collaboration on the films of Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel.

According to Schnabel: “This movie is an accumulation of scenes based on painter Vincent van Gogh's letters, common agreement about events in his life that parade as facts, hearsay, and scenes that are just plain invented. The making of art gives an opportunity to make a palpable body that expresses a reason to live, if such a thing exists.”

The movie opens in Paris, where a frustrated, unsuccessful Vincent (Willem Dafoe) meets the rebellious painter Paul Gauguin (Oscar Isaac), who convinces him to follow the sunlight to the south of France. Funded by his loving brother Theo (Rupert Friend), Vincent sets up in Arles. One day, he puts his tattered boots on the red tile floor of his yellow room and paints them—a masterpiece that now hangs in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

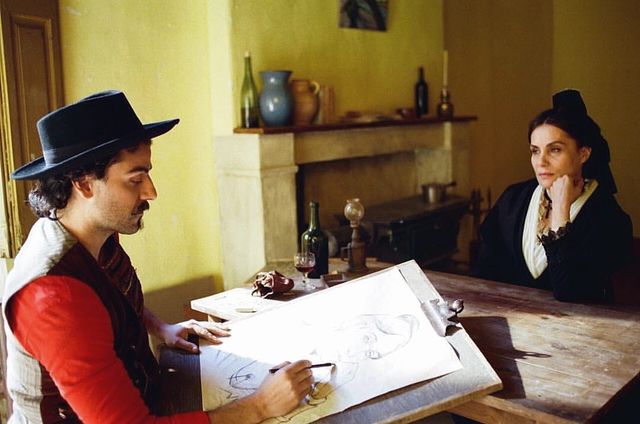

Vincent is soon joined by Paul. (The latter: “We have to start a revolution between painting and reality”). In one memorable scene, they paint side by side, each creating a wildly different version of the same model. Chiding Vincent, Paul says: “Your surface looks like it’s made out of clay. It’s more like sculpture than painting.” When Paul leaves, a despairing Vincent cuts off part of his ear.

The artist tends to be either wandering child-like through nature with an easel, brushes and paint strapped to his back, or immobilized in a straitjacket during his stays in psychiatric hospitals. Eventually, in the final months of his life, he is discharged into the care of Dr. Paul Gachet (Mathieu Amalric) in Auvers-sur-Oise.

At Eternity’s Gate is suffused with breathtaking beauty and stands as an original look at the internal life of the painter. Cinematographer Benoît Delhomme creates the feeling that Vincent is rooted in the earth and rustles with the vibrant bushes and tall grasses in Arles’ expansive fields. A panoramic shot of a wintry landscape dotted with dead, black sunflowers is affecting.

The intense Dafoe is convincing despite the age difference between the actor and the painter. Furthermore, the relationship between Vincent and Theo, who never loses confidence in his brother, is movingly and sensitively dramatized. Essentially, Schnabel seeks to bring out van Gogh’s psychic state, unconcerned with external trappings such as language, a somewhat awkward mélange of French and English.

In one significant segment, Vincent meanders through Paris’ Louvre Museum, contemplating the works of Delacroix, Veronese, Goya, Velasquez and Franz Hals. “They are speaking to van Gogh as he speaks to painters today,” says Schnabel. “There is something there about how artists communicate beyond the grave.”

The movie, however, does not go as far as it might. Biographers and filmmakers alike once assumed that social environment and historical circumstances helped shape the artist, so they explored those elements. Not so today.

Schnabel seems to suggest that the title of his film, At Eternity’s Gate, has an other-worldly meaning. “When facing a landscape I see nothing but eternity,” says Vincent in a voiceover. “Am I the only one to see it?”

In fact, something far more down to earth is involved. At Eternity’s Gate is an oil painting done by Van Gogh shortly before his death in 1890. It is based on his 1882 lithograph Worn Out, inspired in turn, at least in part, by the image of an old, worn-out working class man, depicted by the Belgian socialist artist Paul Renouard in San Travail (Without Work). The painting is not, as the filmmakers imply, merely a foreboding of the subject’s mortality, but a representation of his unemployed condition and physical exhaustion.

Schnabel adopts a rather abstract, ahistorical view of van Gogh, a man of exceptional culture and compassion. However, in his letters, the 19th century painter articulately set out his own social and cultural views.

“I see paintings or drawings in the poorest cottages,” van Gogh wrote, “in the dirtiest corners. And my mind is driven towards these things with an irresistible momentum.” He railed against art profiteers. The “art trade” has become “all too much a sort of bankers’ speculation and it still is—I do not say entirely—I simply say much too much ….I contend that many rich people who buy the expensive paintings for one reason or another don’t do it for the artistic value that they see in them.”

The painter was committed to confronting reality. He argued repeatedly along these lines, included in a letter to Theo: “The most touching things the great masters have painted still originate in life and reality itself.” Van Gogh’s subjects included coal miners, peasants, weavers and manual laborers.

The intensity of his short life—during which he sold only one work out of the 850 he painted—and his tragic death have combined to strike a sympathetic chord with millions of people over the years. He painted landscapes and portraits with urgency and an unparalleled emotionality. If he saw things differently, it was not because the structure of his eye was different to that of previous painters, but because the structure of society was different. Ultimately, he was a child of the great social struggles and transformations of the 19th century. Ignoring these issues makes for a less interesting, compelling film.