Much of the media coverage surrounding the award ceremony conveyed the impression that von Trotta’s main contribution to cinema has been to present strong female characters on screen. The director, however, has never regarded herself as a “woman’s filmmaker.” Von Trotta’s works have never been exclusively devoted to women’s issues, but always dealt with the problems and conflicts of women in the context of broader social issues. The film director has said she regards the denunciations associated with #MeToo as “a kind of reverse witch-hunt: women used to be hunted down, now some men are the target.”

Margarethe von Trotta is one of the most important postwar German filmmakers. Born in Berlin in 1942, she belongs to a generation—born in the shadow of fascism and the Holocaust—that made a conscious decision to oppose the social and political conditions that prevailed in the 1960s. She was part of a generation that also demonstrated against the continuing presence of former Nazis in German politics and opposed the US war in Vietnam. Like many others of her generation, she placed much of her hope in the Social Democratic Party (SDP).

Von Trotta spent her childhood and youth in Düsseldorf before becoming an actress. In Klaus Lemke’s television film Brandstifter (1969) she plays a young woman, Anka, who sets a department store on fire as part of a political protest. The role was modelled on the Frankfurt department store fires of 1968 carried out by individuals who were later to become the Red Army Faction (RAF, better known in the US as the Baader–Meinhof Group) terrorists, such as Gudrun Ensslin and Andreas Baader. Von Trotta collaborated with other directors of the New German Cinema movement, such as Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Volker Schlöndorff, whom she married in 1971.

She began directing in the mid-1970s, influenced by French New Wave films, among others. A number of Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman’s films were also important to her, especially The Seventh Seal (1957), a work that, like some of Bergman’s other films, reflected doubt and pessimism regarding post-World War II conditions of life. Another important inspiration for her work was Bergman’s Sawdust and Tinsel (1953). The film about the aging director of a travelling circus and his young mistress raises the question: can one be more than a mere victim of circumstances? Last year, von Trotta released her own cinematic homage to Bergman.

Like many of her generation, Trotta despised the hypocrisy, self-pity and repression of the past expounded by former Nazis or their apologists. Instead, she wanted to create a new, democratic society through enlightened, and often radical criticism.

She is drawn to vibrant, resilient personalities with a sense of social justice who seek to understand and change their environment, in both the private and social sphere. A number of her films closely explore intimate relationships. A recurring theme is the conflict between sisters, as in her films Sisters, or The Balance of Happiness (1979), Marianne & Juliane (1981) and the television movie Die Schwester [“The Sister”] (2010).

The first film for which von Trotta is credited as co-director is The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum, based on a story by the German author Heinrich Böll, who also worked on the script. The theme of the film is the hysterically charged atmosphere of the 1970s when Baader-Meinhof members were hunted down by the state and many intellectuals—including Böll—were denounced as “terrorist” sympathisers.

One night, Katharina Blum (Angela Winkler), a young woman, takes home a young man, Ludwig (Jürgen Prochnow), who is being watched by the authorities. When police attempt to arrest Ludwig the next morning, he has already given them the slip. Thereupon Katharina is immediately accused of being his accomplice. Entirely innocent, she is helplessly exposed to a massive media campaign of hatred and lies. In utter despair, she shoots the tabloid journalist leading the campaign. At the subsequent funeral, her desperate act is cynically condemned by the journalist’s editor as an attack on freedom of the press. The film, which warned against a conspiracy of police, judiciary, big business and the press, was a great success at home and abroad. (Certain similar themes appear in Fassbinder’s Mother Küsters’ Trip to Heaven, also 1975).

The Schlöndorff-von Trotta effort demonstrated the fragility of Germany’s postwar democracy and the persistence of authoritarian ideas and practice. This was true not only of the 1960s, when student leader Rudi Dutschke was shot amidst a frenetic anti-communist media campaign, but also of the so-called “social democratic” decade, which witnessed a series of attacks on democratic rights in the name of fighting terrorism.

Von Trotta’s first film as sole director was The Second Awakening of Christa Klages (1978). Christa (Tina Engel) is an impulsive young woman with both a big heart and mouth, who seeks social retribution and raids a bank to save her children’s daycare center from financial disaster. In the course of her flight from police, she realises that “expropriation” on a small scale cannot result in fundamental change. Being branded a criminal who risks the lives of the innocent cannot advance progressive aims. “Be patient,” she writes finally on the wall of her room.

Marianne & Juliane

One of von Trotta’s most significant films is Marianne & Juliane, which won the Golden Lion at the Venice film festival in 1981. The film features two very different sisters, Marianne and Juliane, and is based on the story of the Baader-Meinhof terrorist Gudrun Ensslin and her sister Christiane.Born—like the filmmaker—during the Second World War, Marianne (Barbara Sukowa) and Juliane (Jutta Lampe) grow up in a pastor’s family and experience the bigoted and conservative atmosphere of the 1950s. Their father shows a film to his young parishioners. It is the first documentary on the Holocaust to be screened in West Germany, Night and Fog (1956, directed by Alain Resnais).

The film strikes the sisters to the core and becomes a key experience for both of them. The Nazi crimes must never happen again. At a later point, they are both alarmed by similarly horrifying images of the US invasion of Vietnam, which is supported by the German government. Internationally, fascist movements are gaining ground, a development the sisters resolve to oppose with all their might.

Juliane consciously chooses the arduous path of politics of small steps and rejects Marianne’s anarchist-based radicalism. Juliane is the stronger personality in the movie. She is more down-to-earth than her sister who has more in common with a Christian martyr. Juliane realises that the struggle for a just society requires the patience to win over the majority of the population.

Marianne, who was such a gentle child, takes up arms. Juliane becomes a journalist, joins the women’s movement and fights against the existing ban on abortion. When Marianne is arrested, her sister visits her in prison. At first Marianne refuses to talk to her, but Juliane persists and recollections of their childhood bring them closer together. During the prison visits, Marianne accuses her sister of wasting her time on trivial matters. Juliane replies that Marianne romanticises revolutionary action in an arrogant manner. Nevertheless, she remains loyal to her sister and acknowledges the energy with which Marianne endeavours to resolve the problems that drove both of them into politics, even if their political methods differ entirely.

After Marianne dies in prison Juliane demonstrates with the tenacity and energy of her sister that her death could not have been a suicide, thereby going far beyond the narrow horizons of the middle class women’s movement. The death of the three RAF prisoners (Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin and Jan-Carl Raspe) in Stuttgart’s Stammheim Prison in October 1977 was hotly debated at the time and remains unclear until today. There are certainly indications that the leaders of the Baader-Meinhof group were in fact murdered while in Stammheim prison. It is also possible that the RAF trio did commit suicide in a desperate protest against what they alleged was a fascist state.

Journalist Christiane Ensslin, sister of Gudrun Ensslin, met von Trotta personally in 1977, at the funeral of Gudrun and other members of the RAF.

Alarmed about the development of society, but full of political prejudices against so-called “bourgeoisified” workers, many intellectuals not only sympathised with the armed struggle of national liberation movements, such as the Palestine Liberation Organization in the Middle East, but also expressed some sympathy for the actions carried out by the Red Army Faction. Von Trotta temporarily hid a suitcase belonging to someone associated with the RAF and became involved in a campaign for improved prison conditions for RAF members.

In an interview with the Tagesspiegel she said about this period of time: “I may have been too intent on following an ideology, instead of thinking things through to the end. Today I think I got carried away, although I do not reject everything that we believed in back then.”

In common with Fassbinder, who shot the television series Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day about young workers in the early 1970s (and in three of whose films she acted early on in her career), von Trotta demonstrates a sensibility towards the plight of ordinary people. As the offspring of immigrants (her mother was a former German Baltic noblewoman who fled Moscow), von Trotta learnt about the hardships of life as a child. She remained stateless until the mid-1960s and only received full German citizenship following her marriage to Schlöndorff.

Trotta’s film Rosa Luxemburg emerged at a time when a broad anti-war movement was actively opposing Germany’s intensified efforts at military rearmament in the 1980s. Based on actual texts, the film deals with the last 20 years in the life of the outstanding socialist and revolutionary, Rosa Luxemburg. Luxemburg was murdered together with Karl Liebknecht by mercenary soldiers in 1919 during the counterrevolution sanctioned by the Social Democratic Party-led government of the time.

The movie features key political and personal episodes from the life of the revolutionist, demonstrating her enormous courage and political determination.

In 1905 revolution breaks out in Russia. A wave of spontaneous mass strikes spreads across the country. The German SPD leadership, dominated by its conservative trade union wing, reacts defensively. Returning to Berlin from Russia in 1906, Luxemburg (outstandingly played by Sukowa) salutes the revolution. Leading figures in the SPD argue that the situation in Germany is not ripe for the type of mass actions associated with the 1905 Russian revolution. Even aging party leader August Bebel (Jan Biczycki) declares, “You cannot compare the Russian situation with Germany.”

Luxemburg recognises that the Russian Revolution is an expression of a new historical era ending the relatively peaceful period that had lasted for 40 years. The issue is not one of manipulating mass actions from above, as one of her critics claims, but rather of “consciously participating in the historical epoch.” Restricting political work to trade unionism and parliamentary manoeuvres is isolating the party from its real, international workers’ base, Luxemburg argues. The new development of world capitalism requires that the SPD embrace the mass movement in Russia as its own.

Shortly afterwards, at the Mannheim Party Congress in 1906, Luxemburg criticises Bebel’s restraint regarding the stance of the SPD in the event of a German military assault on Russia. His contribution at the congress suggests that nothing can be done. She welcomes the stand taken by the French Socialist Party at that time, which has declared in the event of an outbreak of war, “Rather a popular uprising than war!”

Luxemburg’s passionate speech at a workers’ assembly in Frankfurt am Main in 1913 would be highly topical even today: “The delusion of a gradual trend towards peace has dissipated. Those who point to 40 years of peace in Europe, forget the wars that took place outside of Europe and in which Europe played a role. Those responsible for the war danger hovering over the cultural world are the classes who supported the rearmament mania at sea and on land under the pretext of securing the peace. But also sharing responsibility are the liberal parties that have given up any opposition to militarism. (...) The rulers believe they have the right to decide on such a vital question over the heads of the entire people. (...) When we are asked to raise the weapons of murder against our French and other brothers, we declare: No, we refuse!” [1]

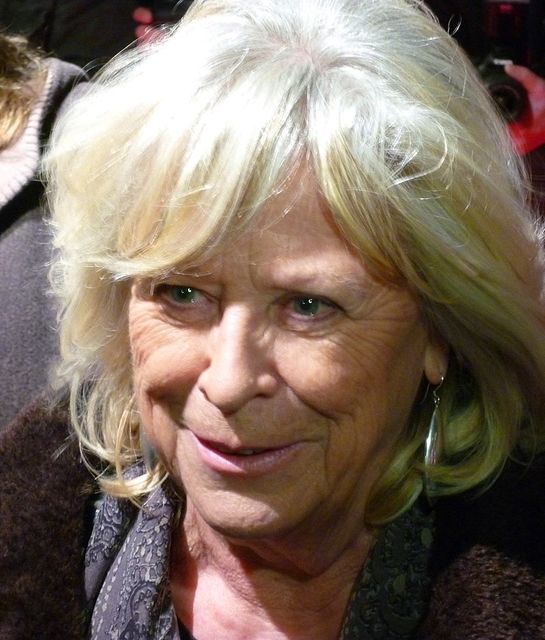

Margarethe von Trotta, 2013 (Photo credit-Roger Weil)

Margarethe von Trotta, 2013 (Photo credit-Roger Weil) Margarethe von Trotta in Fassbinder's The American Soldier (1970)

Margarethe von Trotta in Fassbinder's The American Soldier (1970) Mario Adorf and Angela Winkler in The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum (1975)

Mario Adorf and Angela Winkler in The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum (1975) Jutta Lampe and Barbara Sukowa in Marianne & Juliane (1981)

Jutta Lampe and Barbara Sukowa in Marianne & Juliane (1981)

No comments:

Post a Comment