‘White Whores’: Islam’s Unwavering View on Western Women

In

this Sept. 4, 2017 file photo, a paper heart reading "Dear Maria, we

will never forget you" is hanging near the site of the crime at the

Dreisam river in Freiburg, Germany. A district court later convicted a

young migrant of raping and killing 19-year-old medical student Maria

Ladenburger in a case that fueled a nationwide debate about the

country's migration policy. (Patrick Seeger/dpa via AP,file)

A young woman targeted by what the obscurantist media label an "Asian" Rape Gang told her story after years of being trapped as a young teen after being groomed by Muslim men in the UK. The British woman going by the pseudonym “Kate Elysia” recently revealed

the extent of her sexual victimization by Muslim men. While this

included the numerous details seen in many similar cases -- including drugs, and gang-rapes by as many as 70

men in one night -- her story had an interesting twist to it.

According

to the report: “At one point during her abuse, she was trafficked to

the North African country of Morocco where she was prostituted and

repeatedly raped.” There she was kept in an apartment in Marrakesh,

where another girl no more than 15 was also kept for sexual purposes. “I

can’t remember how many times I’m raped that first night, or by who,”

Kate recounted.

That she

was seen as a piece of meat is evident in other ways: “The Pakistani men

I came into contact with made me believe I was nothing more than a

slut, a white whore. They treated me like a leper, apart from when they

wanted sex. I was less than human to them, I was rubbish.”

What explains the ongoing victimization of European women by Muslim men -- which exists well beyond the UK, and has become epidemic in Germany, Sweden, and elsewhere?

While

these sordid accounts are routinely dismissed as the activities of

“criminals,” they are in fact reflective of nearly fourteen centuries of

Muslim views on and treatment of European women. Nothing in Kate’s

account -- not even the otherwise extreme aspect of taking her to

Morocco to be a sex slave -- has not happened countless times over the

centuries.

For starters, Muslim men have long had an obsessive attraction for fair women

of the European variety. This, as all things Islamic, traces back to

their prophet, Muhammad. In order to entice his men to war against the

Byzantines -- who, as the Arabs’ nearest European neighbors came to

represent “white” people -- Muhammad told them they would be able to

sexually enslave the “yellow” women (an apparent reference to their hair

color).

For

over a millennium after Muhammad, jihadi leaders -- Arabs, Berbers,

Turks, Tatars -- also coaxed their men to jihad on Europe by citing (and

later sexually enslaving) its fair women, as copiously documented in Sword and Scimitar: Fourteen Centuries of War between Islam and the West.

For one example, prior to invading Spain, jihadi hero Tarek bin Ziyad

enticed his men by saying: “You must have heard numerous accounts of

this island, you must know how the Grecian maidens, as beautiful as houris [sexual superwomen are awaiting your arrival, reclining on soft couches in the sumptuous palaces of crowned lords and princes.”

That

the sexual enslavement of fair women was an aspect that always fueled

the jihad is evident in other ways. Thus, for M.A. Khan, a former Muslim

author, it is “impossible to disconnect Islam from the Viking

slave-trade, because the supply was absolutely meant for meeting [the]

Islamic world’s unceasing demand for the prized white slaves” and for

“white sex-slaves.”

And

just as Muslim rapists saw Kate as “nothing more than a slut, a white

whore,” so did Muslim luminaries always describe the nearest white women

of Byzantium. For Abu Uthman al-Jahiz (b. 776), a prolific court

scholar, the females of Constantinople were the “most shameless women in

the whole world ... [T]hey find sex more enjoyable” and “are prone to

adultery.” Abd al-Jabbar (b. 935), another prominent scholar, claimed

that “adultery is commonplace in the cities and markets of Byzantium,”

so much so that even “the nuns from the convents went out to the

fortresses to offer themselves to monks.”

As Nadia Maria el-Cheikh, author of Byzantium Viewed by the Arabs, explains:

Our [Arab/Muslim] sources show not Byzantine women but writers’ images of these women, who served as symbols of the eternal female -- constantly a potential threat, particularly due to blatant exaggerations of their sexual promiscuity. In our texts, Byzantine women are strongly associated with sexual immorality. … While the one quality that our [Muslim] sources never deny is the beauty of Byzantine women, the image that they create in describing these women is anything but beautiful.

Their depictions are, occasionally, excessive, virtually caricatures, overwhelmingly negative … The behavior of most women in Byzantium was a far cry from the depictions that appear in Arabic sources.

But even

taking Kate to Morocco and turning her into a sex slave is a mirror

reflection of history.

Thanks to Ottoman support for the slave-raiding

pirates of North Africa, the so-called “Barbary States,” by 1541

“Algiers teemed with Christian captives [from Europe], and it became a

common saying that a Christian slave was scarce a fair barter for an

onion.”

According to the

conservative estimate of American professor Robert Davis: “[B]etween

1530 and 1780 [alone] there were almost certainly a million and quite

possibly as many as a million and a quarter white, European Christians

enslaved by the Muslims of the Barbary Coast,” of which Morocco was one.

Women slaves -- and not a few men and boys -- were almost always

sexually abused. With countless European women selling for the price of

an onion, little wonder by the late 1700s, European observers noted how

“the inhabitants of Algiers have a rather white complexion.”

It

was the same elsewhere. The slave markets of the Ottoman sultanate were

for centuries so inundated with European flesh that children sold for

pennies, “a very beautiful slave woman was exchanged for a pair of

boots, and four Serbian slaves were traded for a horse.” In Crimea --

where some three million Slavs were enslaved by the Ottomans’ Muslim

allies, the Tatars -- an eyewitness described how Christian men were

castrated and savagely tortured (including by gouging their eyes out),

whereas “[t]he youngest women are kept for wanton pleasures.”

Such

a long and unwavering history of sexually enslaving European women on

the claim that, like Kate Elysia, they are all “nothing more than a

slut, a white whore,” should place the ongoing sexual abuse of Western

women in context -- and suggest that there’s little chance of change

along the horizon.

(Editor’s note: All quotes and historical facts appearing in the above article are documented in the author’s new book, Sword and Scimitar: Fourteen Centuries of War between Islam and the West.)

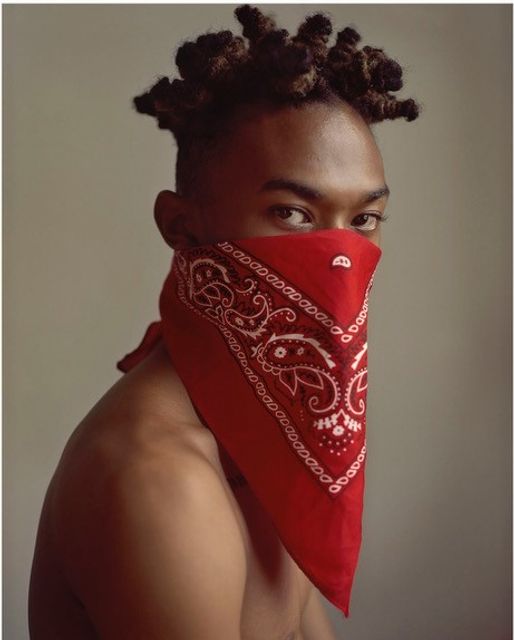

Whitney Museum of American Art

Whitney Museum of American Art  John Edmonds, The Villain, 2018. Inkjet print, 30 x 24 in. (76.2 x 61 cm). [Credit: the artist and Company, NY]

John Edmonds, The Villain, 2018. Inkjet print, 30 x 24 in. (76.2 x 61 cm). [Credit: the artist and Company, NY] Curran Hatleberg, Untitled (Camaro), 2017. Inkjet print, 19 x 23 1/2 in. (48.3 x 59.7 cm). [Credit: the artist and Higher Pictures, New York]

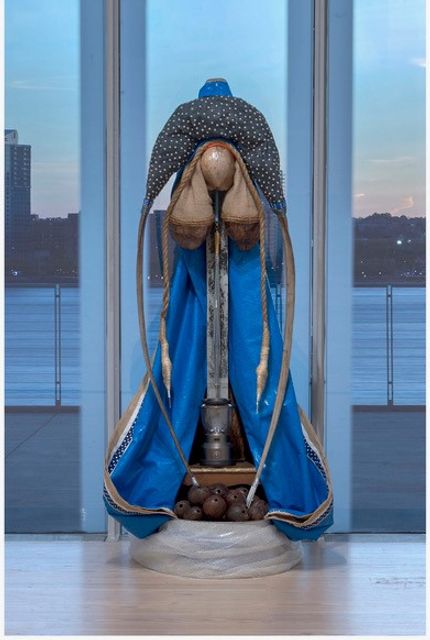

Curran Hatleberg, Untitled (Camaro), 2017. Inkjet print, 19 x 23 1/2 in. (48.3 x 59.7 cm). [Credit: the artist and Higher Pictures, New York] Installation

view of the Witney Biennial, 2019 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New

York, May 17-September 22, 2019). Daniel Lind-Ramos, Maria-Maria, 2019. [Photo credit: Ron Amstutz]

Installation

view of the Witney Biennial, 2019 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New

York, May 17-September 22, 2019). Daniel Lind-Ramos, Maria-Maria, 2019. [Photo credit: Ron Amstutz] Jennifer Packer, An Exercise in Tenderness,

2017. Oil on canvas, 9 1/2 x 7 in. (24 x 18 cm).

Jennifer Packer, An Exercise in Tenderness,

2017. Oil on canvas, 9 1/2 x 7 in. (24 x 18 cm).

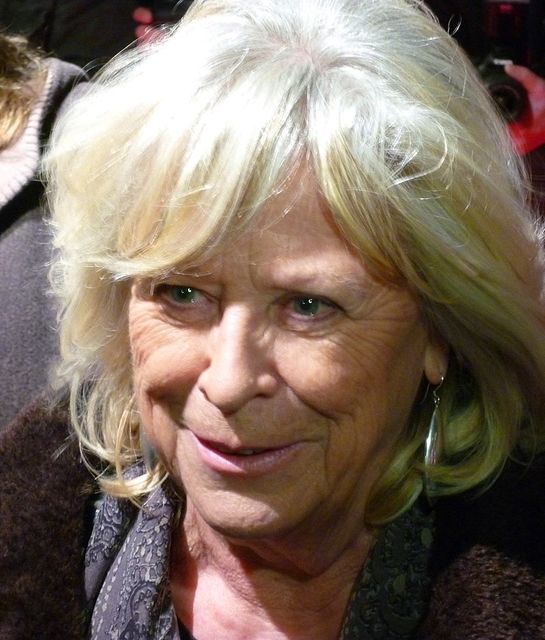

Margarethe von Trotta, 2013 (Photo credit-Roger Weil)

Margarethe von Trotta, 2013 (Photo credit-Roger Weil) Margarethe von Trotta in Fassbinder's The American Soldier (1970)

Margarethe von Trotta in Fassbinder's The American Soldier (1970) Mario Adorf and Angela Winkler in The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum (1975)

Mario Adorf and Angela Winkler in The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum (1975) Jutta Lampe and Barbara Sukowa in Marianne & Juliane (1981)

Jutta Lampe and Barbara Sukowa in Marianne & Juliane (1981)