The #MeToo campaign has launched a vitriolic attack on Roman Polanski’s cinematic masterpiece on the Dreyfus Affair, J’accuse (English title: An Officer and a Spy).

With the full support of France’s banker-president, Emmanuel Macron,

its supporters are working to brand Polanski as a rapist, denounce

viewers or supporters of J’accuse as rape apologists and suppress the film.

The defining characteristic of this reactionary effort is its

contempt for the historical, political and one might add moral issues

bound up with the monumental 1894-1906 legal battle to clear a

French-Jewish officer, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, framed on charges of

spying for Germany. J’accuse currently tops the French box

office, with over a half-million tickets sold in its first week of

showings. Yet #MeToo advocates are aggressively campaigning against this

great work of art, and aligning themselves with far-right positions.

#MeToo supporters rallied at a theater in Paris on November 12,

brandishing signs reading “J’accuse [I accuse] the rapist Polanski,” and

shut down a pre-screening of the film. Since the launch of the film in

France on November 13, they have blocked other screenings in the Paris

area, in Rennes, Saint Nazaire, Bordeaux, Caen and other cities. A

widely publicized slogan of #MeToo demonstrators against J’accuse is “Polanski rapist, cinemas guilty, viewers complicit!”

Leading actors have been forced to cancel appearances to promote the

film, as #MeToo supporters have attempted to block all such efforts.

Jean Dujardin was prevented from publicizing J’accuse on TF1 television, and Emmanuelle Seigner was forced to abandon an appearance on France Inter.

#MeToo supporters and elected officials are trying to impose local

bans on the film. Initially, Socialist Party (PS) official Gérald Cosme

announced a ban on the film in the Seine Saint-Denis department north of

Paris. Cosme was forced to retract the ban, however, after an outcry

from film directors and movie theater staff, who announced they would

defy the ban.

Stéphane Goudet, the director of the Le Meliès theater in Seine

Saint-Denis, addressed a Facebook post to Cosme, stating: “We demand

from officials immediately a letter on the film directors we no longer

have the right to show and the definition of their criteria. Is a

committee of verification of artistic morality planned, as the

democratic freedom of filmgoers is no longer sufficient?” Goudet asked

if famous artists including the novelist Louis-Ferdinand Céline and the

painters Caravaggio and Paul Gauguin were also henceforth banned.

Nonetheless, the #MeToo campaign has continued its hysterical attacks

on the film, posting flyers with pictures of Polanski titled

“Unpunished pedo-criminal.” Disgracefully, France’s guild of authors,

directors and producers (ARP) has announced plans to suspend Polanski,

after he has directed what is arguably his most significant work in a

decades-long career.

Top officials of the Macron government are inciting and supporting

this foul campaign. Minister for Equality between Women and Men Marlène

Schiappa on November 13, and then government spokeswoman Sibeth Ndiaye

the following day, declared they would not see J’accuse. Ndiaye said that she could not view Polanski’s film because she does “not share much with a man facing such accusations.”

Former Minister of Families, Children and Women’s Rights Laurence

Rossignol effectively called for a boycott of the film, arguing that

viewing it is “to offer [Polanski] narcissistic retribution.” While she

said she would not call for the “outlawing” of J’accuse, she said that given the rape allegations against Polanski, “Going to see the film is to throw in the towel.”

The claim that to show, view or support J’accuse is to endorse or excuse rape is a monumental and horrific slander. J’accuse

is not a film about rape, sex or Polanski. It is a faithful recounting

of the struggle against a state cover-up aimed at keeping the innocent

Dreyfus in prison, waged over the course of years by Colonel Georges

Picquart, ultimately together with world-famous novelist Émile Zola and

left-wing political figures.

The Dreyfus Affair eventually engulfed the entire French state

machine and army general staff, nearly bringing down the national

government. The country teetered on the brink of civil war. The affair

separated France into two great camps, the pro-dreyfusards —in which the decisive force was the working class socialist movement led by Jean Jaurès—and the antidreyfusards, whose leading proponent was the anti-Semitic Action française

of Charles Maurras. It was one of the important, early victories in the

20th century of the workers movement against the fascist forces that

would later carry out the genocide of European Jewry during World War

II.

The claim that to be moved by such a powerful film is to be a rape

apologist is disgusting and reactionary. Given the enormous historical

and political significance of these questions, it is tantamount to a

neo-fascistic appeal to racism, anti-Semitism and anti-working class

hatred.

The French state’s encouragement and incitement of the #MeToo campaign against J’accuse

is bound up with its agenda of military-police repression, social

austerity and appeals to extreme-right sentiment. Last year, Macron

hailed Nazi-collaborationist dictator Philippe Pétain as a “great

soldier,” appealing to far-right riot police units as they launched the

largest mass arrests in France since the Nazi Occupation against the

“yellow vest” protests.

Having endorsed Pétain, the Macron government is now seeking to block

honest discussion of the Dreyfus Affair and adopting a hostile attitude

toward Polanski’s film in support of Dreyfus. This is because Pétain’s

Vichy regime had as its main base of support far-right groups founded by

the antidreyfusards, the Action française and Maurras

chief among them. Last year, powerful forces at Macron’s culture

ministry sought, ultimately unsuccessfully, to bring out the complete

works of Maurras.

The anti-Semite Maurras began his career by hailing false documents

prepared against Dreyfus as “absolute truth.” After these documents were

discredited in the 1899 retrial of Dreyfus, he defended them anyway,

declaring he intended to “substitute what was desirable for sad

reality.” That is, since he, the army general staff and the Church desired

to keep Dreyfus in prison, he would continue to defend the charges

against the Jewish officer even though he knew they were lies.

At the end of his career, Maurras hailed the French general staff’s

sudden capitulation to the Nazis in 1940 and Pétain’s coming to power as

a “divine surprise.” Action française members then oversaw

Vichy’s Jewish policy, which led to the deportation of over 70,000 Jews

from France to death camps in Germany and Poland. When he was condemned

to life in prison for high treason after World War II and the fall of

Vichy, Maurras cried out: “This is the revenge of Dreyfus!”

To understand not only the history but also the politics of our era,

it is vital there be an honest, open and uncensored public discussion of

these issues.

The intervention of the #MeToo campaign goes, however, in an entirely

opposite direction—towards censorship based on unsubstantiated

allegations, and the degradation of public debate in line with the

interests, in the final analysis, of the financial aristocracy.

The pretext for the campaign against J’accuse was the publication in Le Parisien,

on November 9, of allegations by photographer and former actress

Valentine Monnier that Polanski raped her in 1975, when she was 18, in

Gstaad, Switzerland. For 44 years, Monnier made no public statement

about the alleged incident, for which the statute of limitations has

expired. She presented no evidence to support her allegation, which

Polanski strenuously denied through his lawyer.

Monnier explained this silence by claiming she had forgotten about being raped but remembered the episode when she heard that J’accuse

was coming out. “The body often communicates what the mind has buried,

until age or an event brings back a traumatic memory,” she said. The

trigger, she claimed, was Polanski’s film: “Can it be tolerated, on the

pretext of a film, under cover of History, to hear someone say J’accuse who branded you with hot iron, whereas you, the victim, cannot accuse him?”

The #MeToo campaign against J’accuse is based on false

premises and unsubstantiated accusations. Monnier did not, as she

implied, suddenly go to the press this month immediately after

remembering she had been raped, shocked by trailers of the upcoming

release of J’accuse. In fact, her statement and the #MeToo

campaign were carefully prepared in discussions with French and US

authorities over several years.

Polanski pleaded guilty in Los Angeles in 1977 to unlawful sex with a

minor, Samantha Geimer, and spent 42 days in prison for psychiatric

examination under a plea deal. However, he fled the United States when a

judge, anxious to burnish his reputation as tough on crime, made

himself guilty of gross misconduct by announcing that he would scrap the

plea deal and sentence Polanski to 50 years in prison. While Geimer has

since said that she forgives Polanski and repeatedly called on the

media to drop its relentless campaign, US authorities are still

vindictively pursuing him to obtain his extradition for political

reasons.

Monnier said nothing of her allegations about a 1975 rape during the

1977 events. The first known mention she made of the alleged 1975

incident was in January 2018 when, inspired by the #MeToo movement

targeting of Harvey Weinstein, she sent letters to Schiappa, French

First Lady Brigitte Macron and the Los Angeles Police Department.

Monnier “wrote again in 2019 about the Ministry of Culture’s financing

of Roman Polanski’s film,” the first lady’s office said.

That such an operation would become the basis of an attempt to censor

a major work of art testifies to the deeply anti-democratic character

of the Macron government and its political allies. As for the #MeToo

campaign, it is unmasked by its engagement in favor of censorship in

line with a government seeking to promote the heritage of fascism.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0ty_M9muolk

Saturday, November 30, 2019

Friday, November 29, 2019

Movie Review: 'Ford v Ferrari' - High Speed Life - 27 Nov 2019

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I3h9Z89U9ZA

Ford v Ferrari

In the mid-1960s, Detroit-based Ford Motor Company decided to attempt to unseat Italy’s luxury sports car manufacturer Ferrari as the reigning champion of Le Mans, the famed French 24-hour sports car race. Ferrari won the event six years in a row, 1960-1965. Ford v Ferrari

Ford v FerrariIn 1963, in order to elevate Ford’s prestige, Vice President Lee Iacocca (Jon Bernthal) pitches Henry Ford II—”the Deuce”—(Tracy Letts) the idea of purchasing the nearly bankrupt Ferrari company. The autocratic Ford agrees and Iacocca is dispatched to Italy to present the proposal to Enzo Ferrari (Remo Girone), the firm’s founder. The latter, after getting a better offer from Fiat, sends Iacocca packing, but not before he caustically derides his American counterpart (“Tell him he’s not Henry Ford. He’s Henry Ford the second”) and his company.

Now Ford is determined to challenge and best Ferrari. From here on, however, the film becomes a match not so much between Ford and Ferrari, but between Ford’s self-serving, myopic management and two mavericks hired to build the Ford race car: a former legendary race-car driver who now designs cars, the American Carroll Shelby (Matt Damon), and the volatile, immensely gifted British race car driver Ken Miles (Christian Bale).

While the Deuce wants to win Le Mans, he is impervious to the machinations of his senior executive vice president Leo Beebe (Josh Lucas), who desires to control the project, whatever the consequences.

Christian Bale in Ford v Ferrari

Christian Bale in Ford v FerrariLe Mans is a tremendous test of endurance, for driver and vehicle, and speed. The winners in 1966 covered 3,010 miles (4,844 kilometers) in a single day, longer than the distance by highway between New York City and Los Angeles. The record distance at Le Mans, set in 2010, is 3,362 miles (5,411 kilometers), or an average speed of more than 140 miles per hour over the course of 24 hours. (Each winning car had two drivers in the first several decades of the event; since 1985 three has become the norm.)

Ford’s win in 1966 (and the following three years), like every other team’s, depended on the cooperation and collaboration of designers, engineers, mechanics, drivers and many others. It represented something of a high-water mark for the postwar American auto industry (or perhaps a last creative gasp), roughly parallel to the success of the US space program. Ford (the only US-based constructor to win the event) has not won Le Mans since 1969, and Ferrari has not taken first prize since 1965. Porsche and Audi have dominated the event in recent decades, with 32 wins between them since 1970.

Automobiles and filmmaking are both products of modern industrial society. The world’s first generally recognized motoring competition took place in 1894. The first public screenings of films at which admission was charged occurred a year later.

However, the artistic union of the two technologies has not necessarily spawned interesting drama. Too often, the dozens of films on the subject (featuring, among others, James Garner, Paul Newman, Steve McQueen, Jeff Bridges and Al Pacino) have been little more than a scaffolding for race-track action and are accordingly forgettable. One exception is Howard Hawks’s relatively modest Red Line 7000 (1965), a film that generates more genuine excitement and intensity out of the cars than in them, or, more accurately, integrates the emotional and physical-mechanical elements into a whole. In artistic fashion, the various racing car sequences, in fact, express or indicate stages of the different emotional entanglements (between the leading male and female characters) and take them forward. But Hawks’s artistry and urgency are in short supply at present, to say the least.

Christian Bale and Matt Damon in Ford v Ferrari

Christian Bale and Matt Damon in Ford v FerrariFurthermore, the highly technical cinematography renders the experience of the film a predominantly sensual one. The heart pounds while the brain remains in low gear. Beyond dramatizing the racing scene, the movie favors the plebian over the aristocratic; American ingenuity over European stagnation and the workingman over the out-of-touch capitalist. Ford v Ferrari has decent but not earthshaking instincts.

Review - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QNLSVfnfV4c

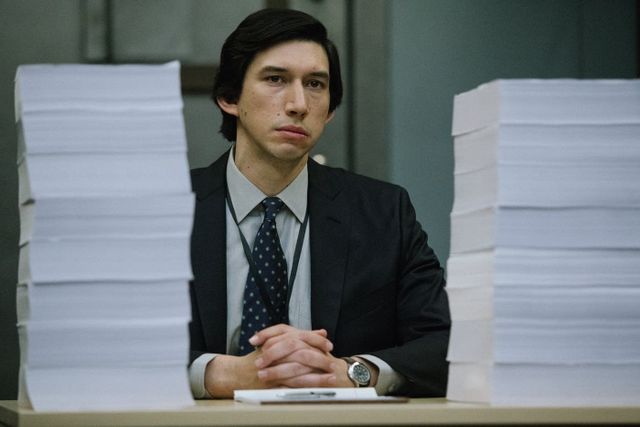

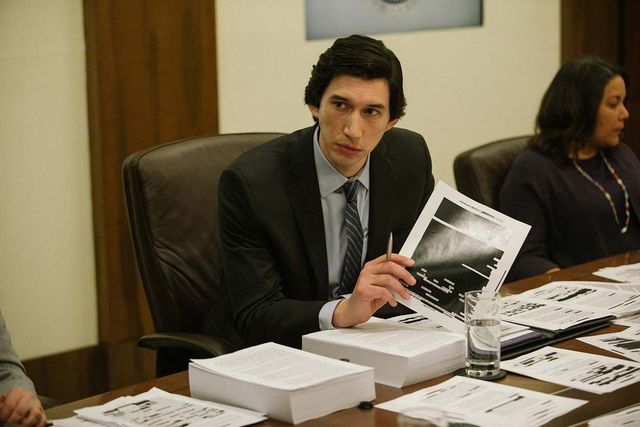

Movie Review - Scott Z. Burn's 'The Report' exposes CIA torture, then absolves the Democrats - 29 Nov 2019

The Report, written and directed by Scott Z. Burns and screened at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival, is a film dramatization of the events surrounding the US Senate Intelligence Committee’s investigation into and writing of a report on pervasive CIA torture under the Bush administration. The film has now opened in the US.

Burns previously produced An Inconvenient Truth (2006), featuring Al Gore, and has written several screenplays for Steven Soderbergh (The Informant!, Contagion, Side Effects, The Laundromat).

The Report

The ReportThe original 6,700-page report remains unpublished to this day, blocked by the CIA and the entire US political establishment on “national security” grounds. Even the fragmentary portions that emerged, however, revealed the fiendish and sadistic methods adopted by American imperialism in its drive to subjugate the world.

Burns’ film importantly points to some of this, but its fatal flaw is its essential attachment to the Democratic Party and, in particular, the reactionary figure of California Senator Dianne Feinstein. It refuses to face up to the reality that the use of Gestapo-like methods by the US military and their defense or cover-up by the ruling elite revealed, as the critics said at the time, that American democracy was in shambles. “The CIA torture program itself was only an extreme expression of a break with bourgeois legality that characterizes every aspect of US policy,” one wrote.

As the movie opens, still under the Bush administration, Dan Jones (Adam Driver), the principal author of the eventual report, has just come from the FBI to work for the Intelligence Committee. Dianne Feinstein (Annette Bening) tasks him with leading an investigation into the CIA’s use of torture after the 9/11 attacks. That work, including the production of an initial report in early 2009, will last some six years.

Annette Bening in The Report

Annette Bening in The ReportThe CIA retains two outside contractors—Air Force psychologists James Mitchell (Douglas Hodge) and Bruce Jessen (T. Ryder Smith), who had no field experience with respect to interrogation and had only prepared a research paper on how CIA agents could resist torture. Nevertheless, in 2006, the value of the CIA’s base contract with the company formed by the psychologists with all options exercised was in excess of $180 million; the contractors had received $81 million by the time of the contract’s termination in 2009.

Horrifyingly, these pseudo-scientists, along with various CIA operatives and officials, devise and oversee techniques, fully in the spirit and tradition of Nazi experimentation, such as sleep deprivation in which a detainee is forced to stand with his arms shackled above his head, nudity, dietary manipulation, exposure to cold temperatures, cold showers, “rough takedowns,” confinement in coffin-like boxes, “rectal hydration” and “rectal feeding,” and the use of mock executions. (One of the operatives, a sinister individual known only as “Bernadette,” played by Maura Tierney, seems to be a composite character largely based on now-CIA Director Gina Haspel.) Guards strip detainees naked, shackle them in the standing positions and douse them repeatedly with cold water. The movie shows one detainee succumbing fatally to the most vicious torture.

Some of The Report’s most chilling and intense scenes depict the torture while dead-faced CIA personnel coldly evaluate the effectiveness of their methods.

This fascistic indifference extends to government figures such as John Yoo (Pun Bandhu), the attorney who pens the notorious “torture memos” that help legalize the EITs. Jones concludes that because the detainees “looked a little different, spoke a different language, it made it easier” for CIA agents to torture them.

Adam Driver in The Report

Adam Driver in The ReportUnder Brennan, the CIA spies on Jones and the other Senate staffers preparing the report, hacking into their computers, thus violating the constitutional separation of powers, the Fourth Amendment ban on arbitrary searches and seizures, and a number of US laws.

The film is relatively hard-hitting in certain ways, but pulls its punches at decisive moments. The depiction of Feinstein as an anti-torture crusader is especially false and even obscene. One of the wealthiest members of Congress and married to an investment banker, the California senator has been for a quarter century a reliable backer and ally of the US military-intelligence apparatus. She has defended the National Security Agency spying programs and denounced whistleblowers such as Edward Snowden, Julian Assange and Chelsea Manning as criminals and traitors. (The movie includes her denunciation of Snowden.)

After the release of the Intelligence Committee report in December 2014 was met with the unapologetic defense of torture by Brennan, along with Bush administration officials, Feinstein issued a groveling statement praising Brennan for showing “that CIA leadership is prepared to prevent this from ever happening again—which is all-important.”

Since its opening in theaters in mid-November, Burns’ The Report has received generally favorable reviews. Unsurprisingly, none of the reviewers refer critically to the overall role of the Democratic Party and Feinstein in particular. Often, in fact, Bening’s performance as the California Senator has been singled out for praise. Variety, for example, writes: “Nowhere is the balance of idealism and practicality, valor and hard-headedness, more exquisitely embodied than in Annette Bening’s superb performance as Dianne Feinstein.” One’s stomach turns.

In a recent interview with the British Film Institute website, Burns expressed explicit support for the CIA, no doubt colored by the Democratic Party’s ever-closer embrace of the military-intelligence apparatus in its conflict with the Trump administration: “I think our story is about a few people at the CIA. Also … there were a lot of people at the agency, then and now, who want to do the right thing, who uphold the law. The intelligence communities in our country and in all of the Five Eyes [intelligence alliance comprising Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and US] are really important. So it’s not a condemnation of the CIA. It’s a commentary on what happens in any government when we lose accountability.” [Emphasis added.]

No one has been punished for the massive crimes carried out under the Bush administration, from an illegal war of aggression in Iraq that claimed over a million lives to the systematic torture of detainees. The inability to hold anyone accountable for the grisly torture program exposes the breakdown of constitutional forms of rule in the United States.

As one critic wrote: “The United States is run by a gigantic military-intelligence apparatus that acts outside of any legal restraint. This apparatus works in close alliance with a financial aristocracy that is no less immune from accountability for its actions than the CIA torturers. The entire state is implicated in a criminal conspiracy against the social and democratic rights of the people, internationally and within the United States.”

The Report would have the viewer believe that the criminal activity by the Bush administration and the Republicans was put a stop to—perhaps haltingly and inadequately—by Obama and the Democrats. In clichéd Hollywood manner, Dan Jones is elevated to the stature of a solitary American hero who saved the day.

This flies in the face of social and political reality. The American war drive continued under Obama using somewhat different tactics and techniques—drone strikes, “kill lists” and the prosecution of new wars in Libya and Syria. The daily headlines, of course, reveal that the eruption of imperialist violence continues under Donald Trump.

The Achilles heel of Hollywood liberal and “left” filmmaking continues to lie in its alliance with one of the parties fully complicit in the crimes and oppression carried out by the American capitalist social order.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hKkTgU37veA

https://archive.is/1KcVH#selection-427.1-427.109

Tuesday, November 26, 2019

Picture Crime - New York Times Considers "Canceling" French Painter Paul Gauguin - 25 Nov 2019

According to Victoria Charles, a biographer of French Post-Impressionist painter Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), the artist died in Atuona, in the Marquesas Islands in French Polynesia, “having lost a futile and fatally exhausting battle with colonial officials, threatened with a ruinous fine and an imprisonment for allegedly instigating the natives to mutiny and slandering the [French] authorities, after a week of acute physical sufferings [from syphilis] endured in utter isolation.”

Upon receiving the news of the death “of their old enemy, the bishop and the brigadier of gendarmes—the pillars of the local [French] colonial regime—hastened to demonstrate their fatherly concern for the salvation of the sinner’s soul by having him buried in the sanctified ground of a Catholic cemetery. Only a small group of natives accompanied the body to the grave. There were no funeral speeches, and an inscription on the tombstone was denied to the late artist.” The bishop subsequently wrote in his regular report to Paris: “The only noteworthy event here has been the sudden death of a contemptible individual named Gauguin, a reputed artist but an enemy of God and everything that is decent.”

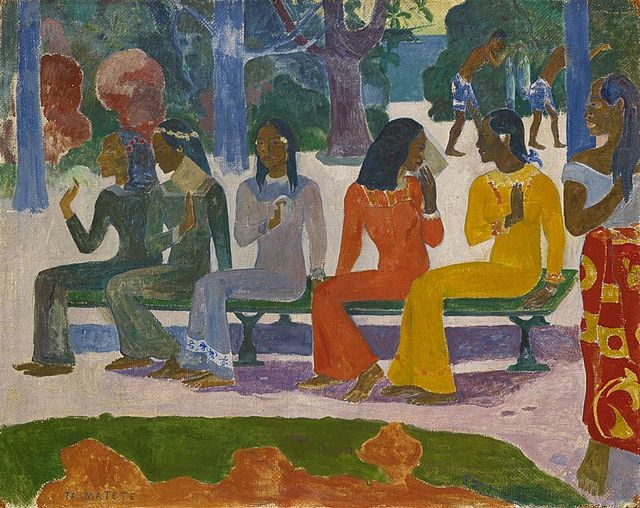

Paul Gauguin, Ta Matete, 1892

Paul Gauguin, Ta Matete, 1892Meanwhile, the opinions of “the bishop and the brigadier of gendarmes” concerning Gauguin’s “contemptible” life-style and activity came to be viewed with disdain—or, more to the point, were simply forgotten. Simultaneously, his paintings of Tahitian women and landscapes, in particular, with all their inevitable contradictions, gained favor among great numbers of people for their brilliant color, expressiveness and sympathy.

However, the contemporary intelligentsia, in its degeneration and decay, unoriginal and uninspired to the core, is effectively reviving the slanders of the aforementioned “pillars of the colonial regime”—now in the name, ironically, of supposed anti-colonialism and feminism.

Objectively, this heavy-handed effort by affluent middle-class layers is directed toward encouraging conformism. Treated outside of any historical or psychological context, Gauguin’s life is turned into a cautionary tale about the dangers of straying from the dictates of today’s petty-bourgeois moralists. Born out of instinctive social fear and economic self-interest, this dishonest accounting of his art and life is a form of intellectual intimidation.

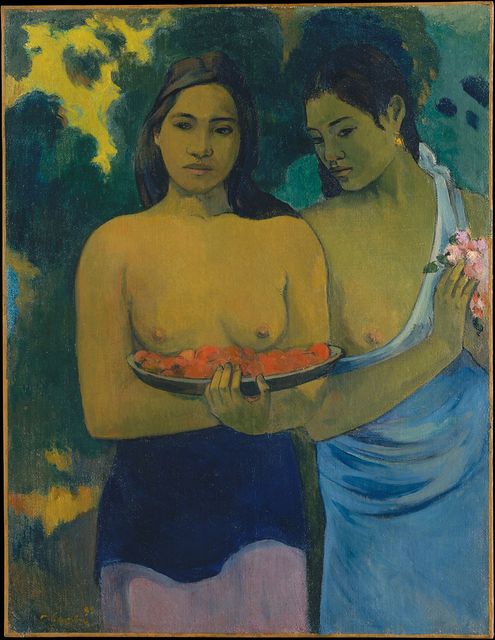

Paul Gauguin, Two Tahitian Women, 1899

Paul Gauguin, Two Tahitian Women, 1899As one such figure, Norma Broude, put it, the “awakening” in the early 1970s in regard to Gauguin’s supposed sins “did little to alter Gauguin’s place in the mainstream canon, if judged by the steady stream of major exhibitions that have continued to appear down to the present day.” She continued: “But it did lead at the time to a vehement rejection and repositioning of Gauguin in the feminist art-historical literature, where he soon came to be castigated, as much for his life as his art, in terms of late-twentieth-century standards and moralities in general and in terms of feminist and postcolonial ones in particular. ” [Emphasis added]

The well-heeled and complacent perpetrators of this campaign do not let the complex facts of Gauguin’s life and career, including his immense sacrifice and suffering, stand in their way.

In the latest attack, the Times published an article November 18 with a headline that posed the question, “Is It Time Gauguin Got Canceled?” The sub-headline continued, “Museums are reassessing the legacy of an artist who had sex with teenage girls and called the Polynesian people he painted ‘savages.’” The new piece, by culture writer Farah Nayeri, forms part of the Times ’ relentless promotion of sexual, gender and racial politics.

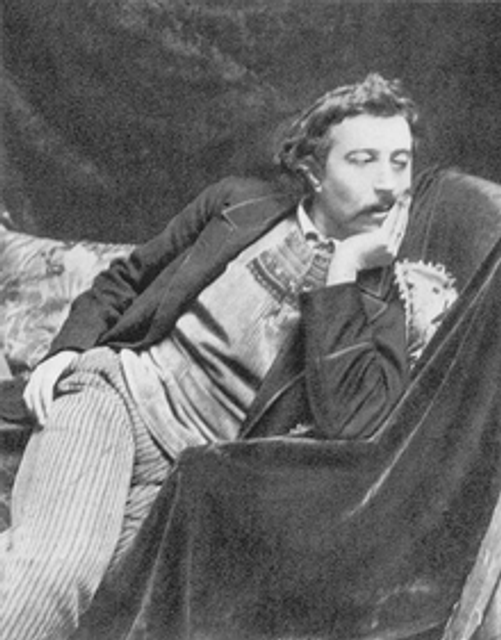

Paul Gauguin, 1891

Paul Gauguin, 1891Who would pose such a “startling”—and foul—question about a major artist? In the past, only deservedly hated censors and authoritarian governments proceeded along these lines. This has been the language and behavior of the extreme right. What is the implied alternative to people “looking at Gauguin?” Should we censor or burn his work to prevent it from being seen by the general public?

National Gallery officials should be ashamed of themselves for even raising such a question. They are capitulating shamefully to the current upper-middle-class obsession with sexual conduct, projected into the past in the case of someone like Gauguin. Victorianism and prudery have reconquered these strata, without much apparent resistance.

Nayeri writes later: “In the international museum world, Gauguin is a box-office hit. There have been a half-dozen exhibitions of his work in the last few years alone, including important shows in Paris, Chicago and San Francisco. Yet in an age of heightened public sensitivity to issues of gender, race and colonialism, museums are having to reassess his legacy.”

One of the know-nothing philistines that Nayeri cites is Ashley Remer, a New Zealand-based American curator, who asserts “that in Gauguin’s case the man’s actions were so egregious that they overshadowed the work.” Nayeri quotes Remer as saying, “He was an arrogant, overrated, patronizing pedophile, to be very blunt.”

Again citing Remer, the Times piece continues: “If his paintings were photographs, they would be ‘way more scandalous,’ and ‘we wouldn’t have been accepting of the images.’”

Nayeri goes on: “Ms. Remer questioned the constant exhibitions of Gauguin and the Austrian artist Egon Schiele, who also depicted nude underage models, and the ways those shows were put together. ‘I’m not saying take down the works: I’m saying lay it all bare about the whole person,’ she said.”

Paul Gauguin, Vahine no te tiare (Woman with a Flower), 1891

Paul Gauguin, Vahine no te tiare (Woman with a Flower), 1891The Times is pursuing a two-pronged campaign. On the one hand, the newspaper gloats over and incites present-day efforts, for example, in France (and elsewhere) to suppress Roman Polanski’s film J ’ accuse ( An Officer and a Spy ) on the Dreyfus affair and anti-Semitism, and on the other, it aggressively urges the exclusion of artists from the past of whom its middle-class constituency is encouraged to disapprove.

What atrocities are still to come? Who will be next in this Vandal-like effort to blot out troubling cultural personalities?

Paul Gauguin was a major artistic figure, whose painting had a genuine influence on the development of modern art. When one considers the occasionally brutal or callous details of his personal life, or simply his bluntness, it is worth considering the harsh and bloody social framework that helped shape him.

The future painter was born in Paris on June 7, 1848, as one biographer noted, “in the midst of the revolutionary events when barricade fighting was going on in the streets of the city.” June 1848 witnessed the mass uprising of the Paris working class and its subsequent murderous suppression by the French army under General Louis-Eugène Cavaignac. More than 10,000 people were killed or wounded in the fighting, including thousands of insurgents—another 4,000 political prisoners were later deported to Algeria. With the final triumph of the status quo in late June, wrote Karl Marx, “the bourgeoisie held illuminations while the Paris of the proletariat was burning, bleeding, groaning in the throes of death.”

Gauguin’s parents were the French-Peruvian Aline Maria Chazal, daughter of the socialist Flora Tristan, and liberal journalist Clovis Gauguin. In the autumn of 1849, for political reasons, the family left for Peru, where Gauguin lived until the age of 7.

Paul and his mother eventually returned to France (his father having died en route to South America), living at first in Orléans in the house of an uncle then under police surveillance due to his role in the 1848 revolution.

Paul Gauguin, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?, 1897-98

Paul Gauguin, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?, 1897-98Gauguin lived a more or less settled, bourgeois life, but began painting in his spare time. He encountered Camille Pissarro, the anarchist Impressionist painter, also a mentor of Cézanne, and other painters during these years. Gauguin began exhibiting works of his own in the early 1880s.

The stock market crash of 1882 had a serious impact on his life. A commentator notes that it “put an abrupt stop to Gauguin’s double life as a broker and an artist.” He lost his employment and moved his family to Copenhagen in 1884 to pursue a business opportunity, which soon failed. Gauguin then returned to Paris, alone, to take up the full-time vocation of artist. His wife and children returned to her family in Denmark. Mette went to work as a translator and teacher.

In the latter part of the 1880s, Gauguin underwent many difficulties, including extreme poverty and deprivation. Famously, of course, he lived with van Gogh in Arles, in the south of France, for nine weeks in 1888. Like van Gogh, he experienced deep frustration and depression (and later, in the 1890s, attempted suicide).

Dissatisfied with Impressionism, which he considered disorganized and insubstantial, finding Paris to be suffocating, and, “in the hopes of retrieving some lost, uncorrupted past from which art could be renewed,” in another biographer’s words, Gauguin traveled to Brittany, Panama and Martinique (where he contracted dysentery and malaria) in 1886–87.

In a letter to a critic written in 1899, Gauguin observed, “We painters, we who are condemned to penury, accept the material difficulties of life without complaining, but we suffer from them insofar as they constitute a hindrance to work. How much time we lose in seeking our daily bread! The most menial tasks, dilapidated studios, and a thousand other obstacles. All these create despondency, followed by impotence, rage, violence.”

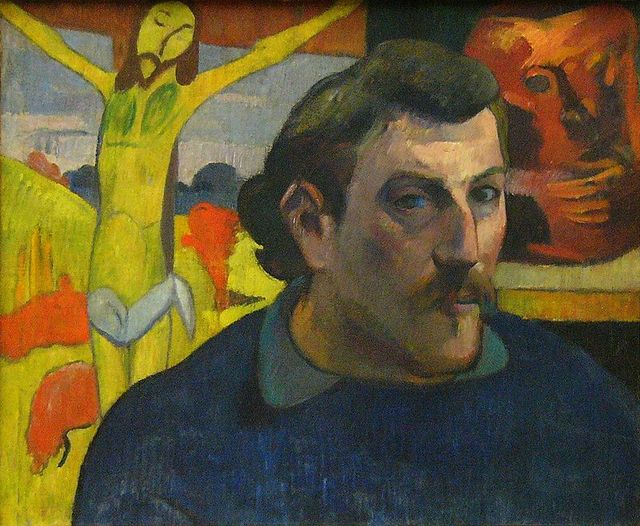

Paul Gauguin, Self-portrait, 1889–1890, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Paul Gauguin, Self-portrait, 1889–1890, Musée d'Orsay, ParisAstonishingly and rather bravely, if foolishly from any “sensible” point of view, Gauguin landed in Tahiti with virtually no money (a public sale in Paris of 30 paintings was enough to cover the cost of the trip) and no knowledge of local customs or the language. His first reaction was disappointment at the degree to which colonization had transformed what he imagined would be an uncontaminated Eden.

French Polynesia, it seemed, “was Europe—the Europe which I had thought to shake off—and that under the aggravating circumstances of colonial snobbism, and the imitation, grotesque even to the point of caricature, of our customs, fashions, vices, and absurdities of civilization. Was I to have made this far journey, only to find the very thing which I had fled?” And later: “The dream which had brought me to Tahiti was brutally disappointed by the actuality. It was the Tahiti of former times which I loved. That of the present filled me with horror.”

His attitude changed somewhat after he removed to a more remote area, where he was entirely reliant on the local people—all his provisions having run out after a day or two!

Gauguin’s description of his life includes quite candid and extended passages about the Tahitian girl, Tehura, he lived with and whom he came to love, and who loved him: “This child of about thirteen years (the equivalent of eighteen or twenty in Europe) charmed me, made me timid, almost frightened me.”

Gauguin returned to France in 1893, leaving his Tahitian “wife” behind. After experiencing further career and personal difficulties, including a definitive break with Mette, the artist returned to Polynesia in 1895. During the last years of his life he often came into conflict with the colonial authorities and the Catholic Church. “In 1903,” one biography explains, “due to a problem with the church and the government, he was sentenced to three months in prison, and charged a fine … He died of syphilis before he could start the prison sentence.”

The reader is free to examine the biographical details and draw his or her own conclusions. Even if one were to determine, however, that Gauguin acted irresponsibly or reprehensibly in Tahiti, to what extent, if any, do the more unseemly facts qualitatively or even identifiably mar his work? Some separation has to be made between the artist and his or her biography, a separation almost always made, for example, in the case of a scientist.

The serious artistic personality is often better than him or herself. Arbitrary and ahistorical moralizing is worse than useless in such cases. Gauguin produced deeply affecting images. No honest viewer could seriously suggest that his depictions of Tahitian life have encouraged colonialist or other backward and reactionary attitudes.

It is true that Gauguin referred to the Tahitians as “savages.” In the first place, however, if it were the case that he was a racist, that would not by itself disqualify his art work. There is still the question of its objective truth as a picturing of life. Unhappily, the roll of artists afflicted with intense anti-Semitism, for example, is quite long, including, of course, Richard Wagner, Edgar Degas and Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

In any event, any serious attention to Gauguin’s work and writings puts the lie to stupid and reductionist conceptions. He could not jump out of his skin any more than anyone else, and there are condescending and prejudiced views expressed in Noa Noa, which one is not surprised to find in the thinking of a 19th century petty-bourgeois European. On the whole, however, Gauguin developed profound admiration and affection for the Tahitians, (and even more so, later, the Marquesans), who befriended and sustained him. Countless passages in the work, indeed its entire thrust and purpose, confirm this.

Moreover, the art world pundits who refer to the painter’s comments about “savages” forget one small detail: for Gauguin, van Gogh and others of his artistic generation and ilk, savagery was something “devoutly to be wished.” In his writings, before and after his departure for Tahiti, Gauguin repeatedly referred to himself as a savage.

In a letter to Theo van Gogh (Vincent’s brother and Gauguin’s art dealer) in 1889, for instance, he remarked: “I am attempting to invest in these figures the savage I see in them, which is also in me.” On another occasion, he wrote, “I try to confront rotten civilization with something more natural, based on savagery.” Near the end of his life, in 1903, he observed, “I am a savage. And civilized people have an inkling of this, for in my works there is nothing that surprises or upsets if it is not this ‘savage in spite of myself.’”

What does this mean, this aspiration to so-called savagery? It was bound up, above all, with the confused reaction of artists and others in the 1880s and ’90s to the development of modern industry, large, crowded cities and mass society itself. As his various comments indicate, Gauguin viewed European society as false, deluded, soulless and corrupt.

He wished, he explained, to “be rid of the influence of civilization … to immerse myself in virgin nature, see no one but savages, live their life, with no other thought in mind but to render, the way a child would, the concepts formed in my brain and to do this with the aid of nothing but the primitive means of art.” This misguided response of artists to the development of modern capitalism was an objective historical question.

In his Nature of Abstract Art (1937), the left-wing art critic and historian Meyer Schapiro, an admirer of Leon Trotsky at the time, wrote persuasively about this phenomenon. It is worth citing his comments at some length:

The tragic lives of Gauguin and van Gogh, their estrangement from society, which so profoundly colored their art, were no automatic reactions to Impressionism or the consequences of Peruvian or Northern blood. In Gauguin’s circle were other artists who had abandoned a bourgeois career in their maturity or who had attempted suicide. For a young man of the middle class to wish to live by art meant a different thing in 1885 than in 1860. By 1885 only artists had freedom and integrity, but often they had nothing else.

… Impressionism in isolating the sensibility as a more or less personal, but dispassionate and still outwardly directed, organ of fugitive distinctions in distant dissolving clouds, water and sunlight, could no longer suffice for men who had staked everything on impulse and whose resolution to become artists was a poignant and in some ways demoralizing break with good society. …

The French artists of the 1880’s and 1890’s who attacked Impressionism for its lack of structure often expressed demands for salvation, for order and fixed objects of belief, foreign to the Impressionists as a group. The title of Gauguin’s picture—“Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?”—with its interrogative form, is typical of this state of mind. But since the artists did not know the underlying economic and social causes of their own disorder and moral insecurity, they could envisage new stabilizing forms only as quasi-religious beliefs or as a revival of some primitive or highly ordered traditional society with organs for a collective spiritual life. This is reflected in their taste for medieval and primitive art, their conversions to Catholicism and later to “integral nationalism.” …

The reactions against Impressionism, far from being inherent in the nature of art, issued from the responses that artists as artists made to the broader situation in which they found themselves, but which they themselves had not produced.Schapiro further noted that it is, in fact, “a part of the popular attraction of van Gogh and Gauguin that their work incorporates (and with a far greater energy and formal coherence than the works of other artists) evident longings, tensions and values which are shared today by thousands who in one way or another have experienced the same conflicts as these artists.”

This sensitivity to the social process and the dilemmas confronting artists at specific moments in history, as well as to the source of their work’s popular appeal, is entirely and eternally a closed book to the identity politics fanatics at the Times. The latter are pursuing a political-ideological course whose success depends on numbing their audience to art and art criticism’s genuinely radical and even subversive sides, and focusing attention solely on their value as weapons in an intramural struggle for position and privilege within the affluent petty bourgeoisie. Gauguin’s life-work is mere additional collateral damage in that warfare.

Paul Gauguin: A collection of 283 paintings (HD)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IdDvbLV5v70

'Double Indemnity' by James M. Cain - Audio Book on Youtube

.............

From Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Double_Indemnity_(novel)

Double Indemnity is a 1943 crime novel, written by American journalist-turned-novelist James M. Cain. It was first published in serial form in Liberty magazine in 1936 and then was one of "three long short tales" in the collection Three of a Kind.[1] The novel later served as the basis for the film of the same name in 1944, adapted for the screen by the novelist Raymond Chandler and directed by Billy Wilder.

Monday, November 25, 2019

Childhood's End - by Arthur C. Clarke - Audiobook on Youtube - 24 Nov 2019

I always loved the title and became curious about the book after seeing a television program about Grand Masters of Science Fiction with director Ridley Scott.

The review of Clarke's work included a long synopsis of 'Childhood's End' with some drawings that I liked. I resolved to look into the story eventually.

Then the work showed up as an audio book offering on Youtube so I listened to the work.

The review of Clarke's work included a long synopsis of 'Childhood's End' with some drawings that I liked. I resolved to look into the story eventually.

Then the work showed up as an audio book offering on Youtube so I listened to the work.

Saturday, November 23, 2019

Friday, November 22, 2019

Movie Review: 'Atlantics' Seeing the Cruel Fate of African Youth Migrating

In different ways, filmmakers are trying to come to terms with certain harsh realities. The traumatic fate of refugees and displaced persons and the cruelty or indifference of the authorities globally have clearly shocked many artists.

Screened in September at the Toronto International Film Festival, Mati Diop’s Atlantics: A Ghost Love Story is an eerie, haunting film that deals fantastically with Senegalese youth lost at sea as they undertake lengthy, dangerous trips to Europe for economic reasons—and those they leave behind. The film is now playing in the US.

An ultra-modern, malevolent tower looms over Dakar, Senegal’s capital. The movie opens with the youthful Souleiman (Ibrahima Traoré) at work on a construction site (Traoré is a construction laborer by trade). The young man and his fellow workers have not been paid in three months. They angrily confront the manager. “Families depend on us!” they tell him, to no avail.

Mame Bineta Sane in Atlantics

Mame Bineta Sane in AtlanticsStrange things begin to occur in Dakar. The marriage bed in Omar’s house catches fire the night of his wedding to Ada. The police detective charged with investigating the blaze is suddenly plagued by a mysterious and debilitating illness. The entire police force is under the influence of the businessman who refused to pay his workers. (The rich man “has done a lot for us,” the detective’s superior reminds him.)

It turns out that Souleiman and the others have come back. They are inhabiting the bodies of the town’s young women, taunting the employer about their unpaid wages. In one of the most memorable scenes in Atlantics, the possessed women force the offending capitalist to dig graves for the drowned. The oppressed are not only oppressed, it turns out, they also have the power to impose their will, a “socially dangerous” lesson to learn.

Diop’s work has a distinct look, that manages to be socially concrete and precise, on the one hand, and disturbingly dreamlike, on the other.

The director told one interviewer (from World of Reel) that she had wanted to learn “why the men in my country wanted to go through the arduous and very dangerous journey” crossing the ocean, and “the only conclusive answers were purely economical. If it were up to them, they would just want to stay in Dakar, be next to their families and friends.”

Atlantics

Atlantics“Although 46 percent of the migration flows from Senegal happen within West Africa—mainly to Mauritania, the Gambia, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali and Niger—Senegal is witnessing an increase of departures from its coasts towards Spain since 2016.”

According to a recent IOM study, what the agency terms “irregular migration” along the Western Mediterranean Route “remains a predominantly young male phenomenon (average age of 31 years old). The study reveals that 57 percent are married and that 36 percent attended primary school and 31 percent Koranic school. Over 70 percent have monthly incomes of between 50,000 and 150,000 FCFA (between 83 and 250 USD), mainly coming from fishing and agriculture. The study also reveals that 45 percent of people who have taken this route have already tried to migrate.”

The IOM also estimated last month that approximately 19,000 migrants have been reported dead or missing in the Mediterranean Sea alone since October 3, 2013.

In the film’s production notes, Diop (whose uncle was the renowned Senegalese filmmaker Djibril Diop Mambéty) explained the origins of her film: “Atlantics is an extension of my first short film shot in Dakar, Atlantiques (2009) . In this short film, I filmed Serigne, a young man who is telling his friends the story of his sea crossing. It was the ‘Barcelone ou la Mort’ [Barcelona or Bust] period when thousands of young people were leaving the Senegalese coast for a better future by attempting to enter Spain. Many perished at sea.

“In 2012, several months after the Arab Spring, riots shook Dakar, a citizens’ uprising took place in Senegal, propelled by the movement ‘Y’en a marre’ [Fed Up]. Most of the young Senegalese wanted to oust [President] Abdoulaye Wade and impose his resignation. This citizen awakening marked me because symbolically it reminded us that Senegalese youth had not entirely disappeared. … For me, somehow, there were not the dead at sea on the one hand and young people marching on the other. The living were carrying the dead within them, who had taken something of us with them when they went. …

“I felt that a very ghostly atmosphere reigned in Dakar and it became impossible for me to contemplate the ocean without thinking of all these young people who had drowned.”

Mati Diop

Mati DiopShe replied: “The tower [in 3D] in the film was inspired by a real architectural project that Wade and [Libyan ruler Muammar] Gaddafi wanted to build together. The first solar tower and the tallest in Africa. When I came across a picture of the architectural project, I felt a mixture of indignation and fascination. How could they spend millions on a luxury tower in the midst of such a disastrous social and economic situation? What fascinated me at the same time was that this tower, in the form of a black pyramid, looked like a war memorial to me. In the end, this project was never realised but it inspired the tower in Atlantics. Today, a new city named ‘Diamniadio’ is being built on the outskirts of Dakar. I shot there, that’s where the film opens. A city designed for an upmarket lifestyle, built by men [the workers] who will not find their place there.”

Atlantics is moving and memorable.

Thursday, November 21, 2019

Listening to the audio book of 'The Maltese Falcon' by Dashel Hammett

After listening to Mark Twain a few days ago, and then young girls book Pollyanna I started to listen to The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett as an audio book on Youtube. What a different outlook and style. The wide eyed girls outlook of yesterday replaced by the direct sentence sharp observation of detective Sam Spade in 1930's San Fransisco.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3b0zWBXlQKU&t=1s

The Maltese Falcon is a 1930 detective novel by American writer Dashiell Hammett, originally serialized in the magazine Black Mask beginning with the September 1929 issue. The story is told entirely in external third-person narrative; there is no description whatever of any character's internal thoughts or feelings, only what they say and do, and how they look. The novel has been adapted several times for the cinema.

The main character, Sam Spade combined several features of previous detectives, notably his cold detachment, keen eye for detail, unflinching, sometimes ruthless, determination to achieve his own form of justice, and a complete lack of sentimentality.

The text is available legally online in Canada - https://www.fadedpage.com/showbook.php?pid=20161221

The Maltese Falcon is a 1930 detective novel by American writer Dashiell Hammett, originally serialized in the magazine Black Mask beginning with the September 1929 issue. The story is told entirely in external third-person narrative; there is no description whatever of any character's internal thoughts or feelings, only what they say and do, and how they look. The novel has been adapted several times for the cinema.

The main character, Sam Spade combined several features of previous detectives, notably his cold detachment, keen eye for detail, unflinching, sometimes ruthless, determination to achieve his own form of justice, and a complete lack of sentimentality.

The text is available legally online in Canada - https://www.fadedpage.com/showbook.php?pid=20161221

Wednesday, November 20, 2019

The Canterville Ghost - by Oscar Wilde - Audio book on Youtube

(1:22:46 min)

A pretty good reading from a Libravox volunteer.

...........

"The Canterville Ghost" is a short story by Oscar Wilde. It was the first of Wilde's stories to be published, appearing in two parts in The Court and Society Review, 23 February and 2 March 1887.[1]

The story is about an American family who move to a castle haunted by the ghost of a dead nobleman, who killed his wife and was starved to death by his wife's brothers. It has been adapted for the stage and screen several times.

Pollyanna - Youtube Audio Book Enjoyment - 20 Nov 2019

I loved the Pollyanna when I was introduced to the story with the movie from the early 1960's.

I listened to the audio book over the last two days.

I also followed along looking at my Illustrated Classic black and white line drawings as I skated up and down the floor while I listened to the audio book playing on my lap top on a stool in the corner.

I've had this book on my shelf for ten years or so, but I had never seen all of the illustrations.

I also followed along looking at my Illustrated Classic black and white line drawings as I skated up and down the floor while I listened to the audio book playing on my lap top on a stool in the corner.

I've had this book on my shelf for ten years or so, but I had never seen all of the illustrations.

Tuesday, November 19, 2019

J’Accuse (An Officer and a Spy): Roman Polanski’s masterpiece on the Dreyfus Affair

19 November 2019

French-Polish director Roman Polanski’s J’Accuse (I Accuse—English title: An Officer and a Spy), released in theaters in France on November 13, is a powerful film recounting of the Drefyus Affair—the historic, 12-year struggle to clear a French Jewish officer, Captain Alfred Dreyfus (1859-1935), unjustly convicted of spying for Germany in 1894. The resulting exposure of criminal behavior implicating virtually the entire French general staff, backed by most of the political establishment, shook the French state to its foundations.(Movie Trailer )

The 86-year-old Polanski’s remarkable film career began more than 60 years ago, in the mid-1950s, with short films made in his native Poland. Some of his important feature films include Knife in the Water (1962), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), Macbeth (1971), Chinatown (1974), Tess (1979), The Pianist (2002), Oliver Twist (2005) and The Ghost Writer (2010). The new film is one of his most significant accomplishments.

J'Accuse (An Officer and a Spy)

J'Accuse (An Officer and a Spy)After years of deepening controversy, the scandal blew apart underlying tensions in French society. During and after the first re-trial of Dreyfus in 1899, governments feared collapse, and France teetered on the brink of civil war.

On the one hand, the dreyfusards invoked ideals of equality and justice proclaimed by the French revolution. Émile Zola (1840-1902), the world-renowned French novelist and author of the celebrated 1885 novel Germinal (inspired by the 1884 Anzin coal miners’ strike), drafted in 1898 his celebrated open letter to then-French President Félix Faure, J’Accuse, published in L’Aurore. In the letter, Zola courageously accused by name top general staff officers and state officials of criminal behavior in framing Dreyfus and then covering up the army’s misconduct.

Alfred Dreyfus c. 1894

Alfred Dreyfus c. 1894On the other hand, the army, the Church and most of France’s political parties defended the unjust verdict against Dreyfus. The antidreyfusards found their most ardent political and journalistic proponents in figures fusing French nationalism, monarchist opposition to the French revolution, anti-Semitism, militarism and hatred of socialism. The archetype of these movements was the proto-fascistic Action française, founded in 1898 and led by Charles Maurras.

In the Dreyfus Affair, Leon Trotsky wrote in 1915, “there was summed up and dramatized the fight against clericalism, against reaction, against parliamentary nepotism, against race hate and militarist hysteria, against backstage intrigues amongst the general staff, against the servility of the courts—against all the despicable forces that the powerful party of reaction could swing into motion to achieve its ends.”

Jean Dujardin and Louis Garrel in J'accuse (An Officer and a Spy)

Jean Dujardin and Louis Garrel in J'accuse (An Officer and a Spy)As the script indicates in the harrowing first scene of the public degradation of Dreyfus (Louis Garrel), everything in the film is based on real events. Polanski’s film not only recounts these events, moreover, but brings to life with extraordinary richness the world of 1890s France, and the courage and principle of those who struggled politically against the state to establish the truth.

The film centers on investigations carried out by Lieutenant-Colonel Georges Picquart (Jean Dujardin), who became head of military counterintelligence after the false conviction of Dreyfus. Over a number of months, Picquart assembled documents conclusively proving Dreyfus’s innocence.

At the center of the conviction of Dreyfus was the charge that he had written the text of a bordereau, a list of military secrets, addressed by a spy to German military officers but which fell into French hands. Government experts admitted that Dreyfus’s handwriting did not match that on the bordereau but dismissed this, claiming Dreyfus was masking his handwriting. This prompted Dreyfus to remark bitterly at trial that he was being convicted because his handwriting did not match that of the spy.

After the conviction of Dreyfus, however, Picquart discovered that the handwriting on the bordereau in fact belonged to another officer, Captain Ferdinand W. Esterhazy (Laurent Natrella), who continued spying for Germany until he finally had to flee to England in disgrace.

Determined to keep Dreyfus on Devil’s Island, the general staff refused to admit its error, protected the spy Esterhazy and tried to discourage Picquart from continuing his investigation. Picquart refused and found himself the target of an unrelenting official campaign to silence him or ship him off to be killed on colonial battlefields. This convinced Picquart to overcome his deep misgivings as an officer about working outside official channels and to provide critical material to Zola (André Marcon) to draft J’Accuse, published in L’Aurore.

By focusing on Picquart’s investigation, Polanski accomplishes a remarkable feat: fitting into a coherent, two-hour narrative most of the key events in a complex scandal obscured by all manner of official lies, provocations and murders. The screenplay is remarkably concise, making effective use of text to help the filmgoer situate himself or herself in the events and understand the large number of characters populating the drama.

The filmmakers have not only taken great pains to accurately recreate the look, feel and manners of the Belle Époque era, but used these elements to create a visually stunning film. This intensity and realism reinforces the drama of a film where most of the main characters find themselves in growing danger of assault, prison or murder.

Polanski’s J’Accuse benefits from wonderful acting that brings credibly to life all the many characters in this complex drama. Grégory Gadebois is excellent as the falsely jocular and deeply cynical Colonel Henry, who all but admitted to Picquart that he helped forge evidence against Dreyfus; conveniently for the army, Henry died in prison in an apparent suicide once his guilt was established.

Emmanuelle Seigner, who is also Polanski’s wife, is remarkable as Pauline Monnier, whose extramarital affair with Picquart the army ends up exposing in an attempt to destroy him. In one moving scene after her husband (Luca Barbareschi) has confronted her and threatened her with divorce, she visits Picquart as he faces imminent arrest and decides she will stick by Picquart, despite the obvious risks.

Above all, Dujardin, normally a comic actor, gives an extraordinary performance as the straight-laced Picquart. A cultured man, who attended classical music concerts and met couriers giving him classified documents in front of statues at the Louvre, Picquart overcame the personal anti-Semitic prejudices he shared with virtually the entire officer corps, fighting with courage and principle. Hauled before the general staff and accused of abetting a Jewish plot to destroy Esterhazy, he told his superiors their investigation was a farce and walked out, slamming the door in their faces.

Jean Dujardin in J'accuse (An Officer and a Spy)

Jean Dujardin in J'accuse (An Officer and a Spy)The film follows events through the 1898 trial of Zola for defamation and Picquart’s testimony at the 1899 re-trial—where the army, trying to calm mounting public outrage by reducing Dreyfus’s sentence but without admitting to wrongdoing, arranged for the ludicrous and contemptible verdict of “guilty of high treason with attenuating circumstances.” Dreyfus was cleared in 1906, though the French army did not ultimately admit to having framed Dreyfus until 1995.

The making of such a film, which genuinely and artistically illuminates one of the great events of European history, is an immense achievement. In an era of mounting influence of far-right parties across Europe, including the relaunch of the Action française that now functions in the periphery of Marine Le Pen’s National Rally, it requires not only integrity and skill, but intellectual courage. It is no exaggeration to say that this film is a masterpiece.

If there is one point that could perhaps be made, it is that while the film powerfully depicts the violent anti-Semitic mobs mobilized by the antidreyfusards, a casual filmgoer would have no idea of the mass dreyfusard support rallied by Zola and Jaurès. This is to some extent due to the film’s focus on the 1894-1899 period. However, the socialist workers movement, which played a key role especially in later years of the Dreyfus Affair, plays no role in the film. As a result, it can seem unclear how Zola, Picquart and their allies could defeat the army’s antidreyfusard supporters, and why the army could not simply respond to Picquart’s insubordination by locking him up.

This does not, however, detract from what the film has accomplished: bringing the Dreyfus Affair vividly and powerfully to life. This is a film that should and must be seen by people around the world, especially amid a new resurgence of neo-fascistic parties and officials across Europe and internationally—from the fascistic rantings of the American president to the attempts in German media to revise the history of Nazism in order to revive German militarism.

One scene at the beginning of the film in which Picquart receives secret files from his predecessor as head of military counterintelligence, Colonel Sandherr (Eric Ruf), is especially chilling. Dying of syphilis, Sandherr tells Picquart one file is critical—it has the list of thousands of political opponents to be rounded up and arrested to purify the nation in case of war. He adds that Jews should be rounded up, also.

Fascist rule and the Holocaust in France was largely the coming to power of the antidreyfusards. Maurras, who started out in journalism hailing Henry’s false documents incriminating Dreyfus as “absolute truth,” ended as the godfather of the Nazi-collaborationist Vichy regime, after the French army suddenly capitulated to the Nazis in 1940, in the first year of World War II. He was widely seen, correctly, as the intellectual inspiration for the entire fascist ruling clique around dictator Philippe Pétain.

Action française members who played key roles in the collaboration included Raphaël Alibert, Xavier Vallat and Louis Darquier, who oversaw various stages of Vichy’s genocidal anti-Jewish policy; the infamous pro-Nazi propagandist Robert Brasillach; Vichy Finance Minister Pierre Bouthillier; and countless lower-ranking officials, thugs and murderers.

Significantly, when Maurras was sentenced to life in prison for high treason at the end of World War II and the fall of the fascist regime, he cried out: “This is the revenge of Dreyfus!”

Even so many decades later, none of the fundamental issues involved in the Dreyfus Affair have been resolved. Significantly, the right-wing hysterics of the #MeToo campaign, in contact with French President Emmanuel Macron’s government and authorities in America, have launched a ferocious campaign against J’Accuse, trying to prevent the showing of a film recounting one of the most critical battles in the history of the socialist movement. Disgracefully, the film has no distributor at this point in the US or the UK.

The history of the Dreyfus Affair is of enormous importance today. After French President Emmanuel Macron hailed Pétain as a “great soldier” last year while launching police repression of social protests, and as forces in the French Ministry of Culture try to re-publish the works of Maurras, it is clearer than ever that it does not solely belong to the past. Polanski’s film on this victory of truth against nationalism and militarism is a significant contribution that deserves a wide audience.

(Documentary on Dreyfuss Affair ) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cgIUm2X6K1s&feature=emb_title

Monday, November 18, 2019

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court - Audio Book - Et Cetera - 18 Nov 2019

I was looking for an audio book on Youtube. I started paying for Youtube Premium and use the site with no advertisements. Things load really fast. Using Youtube for an audio file from Librivox is actually easier on Youtube. Often a whole book is loaded onto a Youtube file, so one can listen to the book for a while without constantly clicking, as with Librivox, for a new chapter.

A lot of the titles of audio books I see listed on Youtube do seem to be from Librivox originally. I saw a relatively new upload of the book 'A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court' by Mark Twain listed with a line drawing of a knight charging a man in a modern business suit up a tree and decided to give the work a listen. A good reading. I have seen the Bing Crosby movie of the work and have had a copy sitting on my bookshelf since high school. It was a good reading. I listened to the whole work over the next three days.

I found my paperback copy from high school - forty-five cents for the book.

I also looked through all of my illustrated classics for the version I thought I remembered.

I watched a cartoon from 1970 that was half decent - a noted the voice of Orson Bean as the main character because I also am familiar with his voice as Bilbo Baggins in an 1970's cartoon of The Hobbit.

I also got some enjoyment out of a live action drama from 1978 :

A lot of the titles of audio books I see listed on Youtube do seem to be from Librivox originally. I saw a relatively new upload of the book 'A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court' by Mark Twain listed with a line drawing of a knight charging a man in a modern business suit up a tree and decided to give the work a listen. A good reading. I have seen the Bing Crosby movie of the work and have had a copy sitting on my bookshelf since high school. It was a good reading. I listened to the whole work over the next three days.

I also looked through all of my illustrated classics for the version I thought I remembered.

I watched a cartoon from 1970 that was half decent - a noted the voice of Orson Bean as the main character because I also am familiar with his voice as Bilbo Baggins in an 1970's cartoon of The Hobbit.

Sunday, November 17, 2019

Why do people sometimes prefer Dom/sub relationships?

Why do people sometimes prefer Dom/sub relationships?

D/s is one aspect of the wider category of BDSM (Bondage and Discipline, Dominance and Submission, and Sadomasochism), sometimes also known as kink. Some people are into all of the things listed under BDSM, and some only some of them. D/s is generally distinguished from SM because it is more about power than about physical sensation (although some use these terms more interchangeably).

In D/s activities one person generally dominates the other, or has power over them, therefore people tend to prefer D/s if they find a power dynamic to be exciting in some way. Of course it is pretty common for sex and power to be mixed together in our culture. For example, a lot of romance fiction involves people being rescued from peril or being swept away by somebody more powerful, and a lot of people fantasise about having the power of being utterly desirable to their partner.

What is involved in a Dom/sub relationship?

If somebody identifies as being into D/s, or having a D/s relationship, then they probably include power play in their sex life, and perhaps in other aspects of their relationship. People can identify as dominant, submissive, or switch (which means that they are sometimes dominant and sometimes submissive). It might be that people stick to the same roles each time they play together, or that they take different roles on different occasions.

For most people, being D/s will be something that they only do some of the time (for example, just in pre-arranged scenes – often, but not always, involving sex). Such scenes could involve any kind of exchange of power. For example, the submissive person might serve the dominant one food, or give them a massage; the dominant person might order the submissive one around or restrain them or punish them in some way; people might act out particular power-based role-plays such as teacher and student, cop and robber, or pirate and captive.

Some people who are into D/s might have longer periods, such as a holiday, where they maintain their power dynamic. And a few have lifestyle or 24/7 arrangements, where one person always takes the dominant, and the other the submissive, role. However, even in such cases much of their everyday life will probably not seem that different to anybody else’s. How does it differ to the traditional ‘vanilla’ relationship?

This depends very much on how important it is in the lives of those involved. Some D/s relationships would look very much like a vanilla relationship but just with a bit more power-play involved when people have sex. Others would have something of the D/s dynamic in other parts of the relationship. However, it should be remembered that most vanilla relationships have specific roles (e.g. one person takes more responsibility for the finances, one person is more outgoing socially, one person does more of the looking after, one person takes the lead in sex). In D/s relationships those things tend to be more explicit, but perhaps not hugely different.

So perhaps the main difference is in the amount of communication. Most people involved in BDSM stress the importance of everything being ‘consensual‘ so there will probably be much negotiation at the start about the things people do and do not enjoy, and the ways in which the relationship will be D/s. Checklists and contracts can be useful ways of clarifying this. So, for example, there may be limits about the kinds of activities and sensations people like, whether they enjoy role-play or not, and which aspects of the relationship will have a D/s element.

Why do so many people have misconceptions of this type of relationship?

The media portrayal of BDSM has tended to be very negative, often associating it with violence, danger, abuse, madness and criminality. Research has shown that actually people who are into BDSM are no different from others in terms of emotional well-being or upbringing, and that they are no more likely to get serious injuries from their sex lives, or to be criminal, than anybody else.

Often the media also focuses on the most extreme examples, such as very heavy and/or 24/7 D/s arrangements, rather than the more common relationships where there are elements of D/s. For these reasons people may well have misconceptions about D/s relationships. This is why it is useful to get a range of experiences out there in the media – so people can have more awareness of the diversity of things involved and the continuum (e.g. from light bondage and love bites to more scripted scenes and specifically designed toys). How do couples go about beginning a relationship like this?

A good idea for all people in relationships, whether or not they are interested in D/s, is to communicate about what they like sexually early on, and more broadly about what roles they like to take in the relationship. Often people just assume what they other person will enjoy or how they would like the relationship to be.

For example, one good activity from sex therapy and from the BDSM community is to create a list as a couple of all of the sexual practices that either of you is aware of, and then to go down it writing ‘yes’, ‘no’, or ‘maybe’ about whether it is something that interests you, and sharing your thoughts. It can also be good to share sexual fantasies or favourite images/stories and to talk about whether (and, if so, how) they might be incorporated into your sex life (the Nancy Friday and Emily Dubberley collections of sexual fantasies can be helpful with this). It is very important that people only do things that they really want to try (rather than feeling coerced into certain activities) and that it is accepted that there will likely to be areas which aren’t compatible as well as those that are.

BDSM communities and websites are a great place to look for more information from those who have been involved in these kinds of practices and relationships. Also local fetish fairs and kink events often include demonstrations and workshops. There is more in my books Enjoy Sex and Rewriting the Rules about communicating about sex and relationships. Some people have a BDSM relationship outside of an existing ‘vanilla’ relationship.

What effect can this have on a marriage or couple relationship?

Again this varies. Although it isn’t always out in the open, many couples have arrangements where they are open to some extent (e.g. monogamish couples, the ‘new monogamy’, open relationships, swinging, polyamory, and ‘don’t ask don’t tell’ agreements).

Having different sexual desires is one reason why some couples open up their relationship to one or both of them being sexual with another person. If this is communicated about clearly, kindly and thoughtfully, it can work perfectly well. The important thing again is kindness and communication. In regards to the hit book 50 Shades of Grey, many husbands have bought this for their wives and girlfriends. What does this say to them, and how would you help a couple who want to get more involved in this sort of lifestyle but don’t know how, or they are too shy to approach it?

The kinds of conversations and activities mentioned above are a great idea. One of the good things about 50 Shades of Grey is that it has opened up this kind of conversation for many people. However, it is important not to assume that the only form of BDSM is the one described in the book. In a heterosexual couple it may well be that the woman is more dominant, for example, or that both people switch roles, and the things that they enjoy may well be different to the ones which the characters engage in in the book.

If you want to read more about different practices and how to do them, then there are lots of good books available about BDSM. Dossie Easton and Janet Hardy’s books The New Topping Book and The New Bottoming Book are great places to start, as is Tristan Taormino’s The Ultimate Guide to Kink.

For couples who are really struggling to communicate about sex, or who have very different desires and are finding it hard to reconcile this, it might well be useful to see a sex and relationship therapist for a few sessions. The Pink Therapy website includes many kink-friendly therapists.

https://www.reddit.com/r/Submissive_/comments/dxlqsg/why_do_people_sometimes_prefer_domsub/

https://archive.is/JGiSc

D/s is one aspect of the wider category of BDSM (Bondage and Discipline, Dominance and Submission, and Sadomasochism), sometimes also known as kink. Some people are into all of the things listed under BDSM, and some only some of them. D/s is generally distinguished from SM because it is more about power than about physical sensation (although some use these terms more interchangeably).

In D/s activities one person generally dominates the other, or has power over them, therefore people tend to prefer D/s if they find a power dynamic to be exciting in some way. Of course it is pretty common for sex and power to be mixed together in our culture. For example, a lot of romance fiction involves people being rescued from peril or being swept away by somebody more powerful, and a lot of people fantasise about having the power of being utterly desirable to their partner.

What is involved in a Dom/sub relationship?

If somebody identifies as being into D/s, or having a D/s relationship, then they probably include power play in their sex life, and perhaps in other aspects of their relationship. People can identify as dominant, submissive, or switch (which means that they are sometimes dominant and sometimes submissive). It might be that people stick to the same roles each time they play together, or that they take different roles on different occasions.

For most people, being D/s will be something that they only do some of the time (for example, just in pre-arranged scenes – often, but not always, involving sex). Such scenes could involve any kind of exchange of power. For example, the submissive person might serve the dominant one food, or give them a massage; the dominant person might order the submissive one around or restrain them or punish them in some way; people might act out particular power-based role-plays such as teacher and student, cop and robber, or pirate and captive.

Some people who are into D/s might have longer periods, such as a holiday, where they maintain their power dynamic. And a few have lifestyle or 24/7 arrangements, where one person always takes the dominant, and the other the submissive, role. However, even in such cases much of their everyday life will probably not seem that different to anybody else’s. How does it differ to the traditional ‘vanilla’ relationship?

This depends very much on how important it is in the lives of those involved. Some D/s relationships would look very much like a vanilla relationship but just with a bit more power-play involved when people have sex. Others would have something of the D/s dynamic in other parts of the relationship. However, it should be remembered that most vanilla relationships have specific roles (e.g. one person takes more responsibility for the finances, one person is more outgoing socially, one person does more of the looking after, one person takes the lead in sex). In D/s relationships those things tend to be more explicit, but perhaps not hugely different.